Agnolotti, cappelletti, ravioli... These are just three of the numerous types of filled pasta, a speciality of Italian cuisine and one of its major triumphs. Each region has its own traditional recipes, but discovering their origins is a real mystery

While experts generally agree on how pasta spread through the independent states of Italy that preceded unification, it’s a real mess when it comes to explaining the origins of these delicious pasta envelopes with their thousand different fillings, served dry and topped with sauce or presented in a delicious broth.

The uncertainty is worthy of Hamlet. Could the various forms of filled pasta that we know today be a reinterpretation and inspired by the numerous types of dumpling originating in Mongolia, Persia or China?

Regional tradition is strong here, and each person tells the story from their own point of view, citing myths and legends that in some cases are truly bizarre.

CHINESE ORIGINS

The strangest story has to be around the origin of the most famous ravioli from the North of China, jiaozi, which are said to have been invented by the physician Zhang Zhongjing during the era of the Han dynasty (25–220 d.C.) as a traditional Chinese medicine.

These delicious parcels were originally known as jiao’er, meaning “tender ears” because they were used to treat people with frostbitten ears! Zhang Zhongjing wanted to provide remedies to impoverished people who, lacking warm clothes and sufficient food, were apt to become ill during the harsh winters.

He prepared cups of restorative broth made with mutton and herbs and in each placed two jiao’er made with meat, garlic and ginger.

The treatment lasted from the winter solstice until the Spring Festival (chūnjié), which marks the Chinese New Year.

The remedy proved to be so effective that even today, when Chinese families come together for the most important celebration in the Chinese calendar, they prepare hundreds of ravioli as a symbol of good luck for the new year.

MONGOLIAN ORIGINS

Legend apart, it’s more likely that the concept of the “raviolo” (the singular of “ravioli”) was an invention of the Mongolian empire based on steamed buns known as mantou, which are still enjoyed today, from the manti of Turkey to the mandu of Korea, as a result of their diffusion along the Silk Road.

According to this theory, Chinese jiaozi are the result of a natural evolution that took place across centuries in the hands of the Uyghurs of Xinjiang province, who transformed this steamed bun filled with meat into a little stuffed raviolo.

PERSIAN ORIGINS

The third hypothesis posits that Italian filled pasta was inspired by something very similar in form and concept (though not in the filling or accompanying sauce) to the dumplings prepared in ancient Persia under the Sassanid Empire (651 d.C.) which stretched from the Eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia.

Italian cuisine boasts the merit of successfully adopting a huge range of creative ideas from distant lands over the centuries and reinventing them in its own way, favouring ingredients and tastes that make them clearly identifiable and unique in the world.

As an illustration, we only have to look at the shapes and preparation methods of specialities such as culurgiones from the Sardinian region of Ogliastra, which are incredibly similar to the momo dumplings and broth of Nepal, or Ligurian cheese-filled pansotti that closely resemble certain Hong Kong dim sum.

A NOTE ON FILLINGS

While the appearance and folding techniques of Italian ravioli may be relatively similar to those found in Asia, things are vastly different when it comes to fillings and accompanying sauces.

Vegetable fillings such as Chinese cabbage or water chestnuts, often flavoured with ginger and garlic, give way to potatoes flavoured with mint, wild spring herbs or, in the case of Ferrari cappellacci (known as caplaz in the local dialect), autumnal pumpkin.

Yoghurt-based sauces are replaced by melted butter, sometimes flavoured with herbs or cream, and dumplings with fillings of prawns or crabmeat are replaced by fillets of grouper, bream, sea bass or freshwater fish.

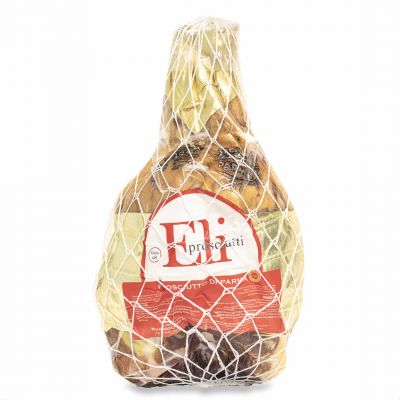

When it comes to meat, Italy certainly share the Chinese taste for pork, if not for mutton! Italians make fillings with beef, chicken, Parma ham, parmesan and mortadella... which brings us to Emilia, where menus talk of cappelletti and anolini - a question of how the pasta is cut.

Generally speaking, spices take a back seat in Italy and herbs take centre stage.

Broths made from chicken, capon or beef are more commonly found in northern Italy and closely resemble soups from Yunnan province, while the preference in the south is for thick, aromatic tomato sauces, sometimes concentrated or stewed with pork ribs. Why not?

LIGURIAN PANSOTTI | Liguria

In some ways, pansotti could be considered the missing link between East and West, not least because of their shape, which are fairly similar to Asian dumplings.

Some people say that the walnut sauce they’re served with is a reworking of Turkish Tarator sauce, made with yoghurt, garlic and walnuts, and that it was imported and adapted by the Genoese from Galata Saray, the Genoese quarter of Istanbul.

DIM SUM | Hong Kong

Legend has it that a Chinese emperor, reaching Hong Kong after weeks of travelling, arriving on the Island of Nine Dragons, asked the local cook tasked with serving him to cook him something special that would bring joy to his heart (dim sum), or else he would be beheaded.

The cook was terrified, and, not knowing the Emperor’s taste, decided to please him with 100 types of dumplings, each one different from the rest.

The Emperor found “joy in his heart” and from that time on made the cook bring a feast of dim sum to the table. And so his salvation became his punishment.

Vittorio Castellani

journalist known as “gastronomade”

(gastronomic nomad)