“The lowest price is not always the fairest one” used to write in its advertising campaigns NaturaSì, an Italian company specialised in production and distribution of organic food.

A price is fair - and consequently the supply chain is sustainable - only if all the protagonists are properly rewarded.

This has been a very hot topic in Italy in the last weeks, since Sardinian shepherds have been pouring milk on the town streets for days, to protest against the very low price of their product.

“Milk price is so low that we’d rather throw it away than sell it to industrialists for almost nothing”, they say, stalling cheese production.

In his article “The warriors of milk”, Carlo Petrini, founder of Slow Food, quotes Michael Pollan that, in “The Omnivore’s Dilemma”, a book written more than 10 years ago, defined cheap food as an illusion: what is not paid by consumers would be paid in terms of impact on the environment and health.

Unfortunately it is not the first time we are experiencing this kind of protest in the food industry: it reminds us the cut of orange groves to make wood, and many others.

The run-up to the lowest price, in so many food supply chains, ends up being discharged on the weakest link in the chain: the shepherds, in this case, but many other times the farmers or the breeders.

Those who take care of the land and animals, with passion, respect and hard work, often carrying out secular traditions, are not always fairly payed.

To escape the price fall several breeders - shepherds for generations - chosed to start transforming milk within the same farm.

It is a story we have heared repeated many times in the last years, from Asiago Plateau in Veneto to Marchesato di Crotone, in Calabria region. Breeders who start transforming their milk, to give value to the raw material and to give a future to their farm.

And vice versa producers who start to breed their animals, to control the quality of milk or meat, knowing exactly where and how animals live, and what they eat.

Craftsmanship is no longer enough, there’s the need to integrate the supply chain. And the short chain has an increasingly important weight in our selection criteria, first of all because it allows the producer a direct control over the quality of raw material.

“Fermier” producers, we defined them provocatively exactly two years ago at Taste, a food fair in Florence, where we presented a selection of short-chain pecorino cheeses. In France a cheese can be defined as fermier when it meets three requirements:

(1) it is produced with raw milk and artisanal methods (2) in the dairy within the same farm (3) using exclusively the milk of their animals.

“Anyone who can produce and transform his product within his company has greater margins as well as greater satisfaction and recognition”, writes Petrini, underlining the importance of integrating the supply chain.

“Short chain” is one direction of sustainable agriculture development, together with the “multifunctional farm”, able to cultivate different products, to use manure from their animals as fertilizer, to be at the same time an educational farm and a shop, perhaps offering also hospitality.

Cortese brothers on the Asiago plateau, Borgoluce and Casa Cason in Veneto region, Lischeto farm in Tuscany, Maiorano farm in Calabria are just few examples of producers who have chosen to integrate the supply chain. As well as Bussu brothers and Leonardo Pulinas in Sardinia.

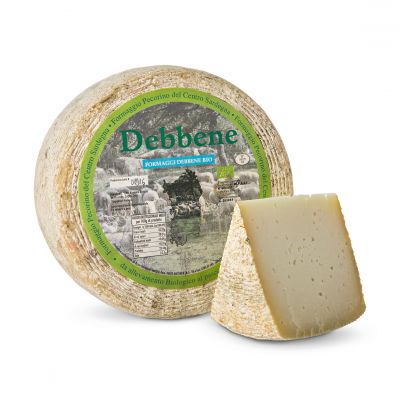

Gianfranco and Salvatore Bussu are first of all shepherds. Debbene Dairy is located on the Campeda plateau, in Sardinia, and more precisely in Macomer, in the province of Nuoro. The cheeses are produced exclusively with raw milk obtained from 1800 owned Sardinian sheep, bred in the wild on the pastures of the plateau.

The sheeps live on 200 hectares of pasture (50% arable land and 50% natural pasture), rich in native grasses, e.g. Campeda trifolium, spontaneous ryegrass, chives, which give the cheese a unique flavor. The feeding is integrated only with the addition of organic forage produced within the same farm, without chemical fertilizers. Even the rennet used in cheese-making is produced from lambs of the Sardinian breed. The animals are never treated with antibiotics, the company has been certified “organic” for over 15 years.

Also Luigi Pulinas farm is a “closed-circuit company” - as Leonardo defines it - because it manages the whole production chain, from farming to breeding to cheese-making and aging. The animals - about 600 Sardinian-bred sheep - live in their own lands in the wild, feeding on the pasture in a natural way.

The value of short production chain lies precisely in the possibility of controlling every phase of production, starting from farming and breeding.

The farm has been run by the Pulinas family for generations, the memory get lost back in the centuries. Today it is managed by Leonardo, together with his brother Antonio, using the same cheese-making techniques handed down by their ancestors, with the copper boiler and the wooden curd-knife.

Raw milk, craftsmanship, respectful breeding, pasture biodiversity are the common features of “our” fermier producers. If we share these values we should also be willing to pay a fair price that rewards them.

Being aware that each of us has the possibility to influence the food system, purchase after purchase, choice after choice: a power we should be more aware of, but also a responsibility we can no longer escape.

Martina Iseppon

Marketing Director